Desert Loop Trail

On the Desert Loop Trail, enjoy a rugged half-mile hike that winds downhill and back up through the Sonoran Desert. Along the way, you’ll encounter javelinas, coyotes, and lizards in naturalistic habitats, discover the fascinating adaptations of the agave plant, and learn to identify native legume trees — all while immersing yourself in the beauty of the desert landscape.

Currently on exhibit around the Desert Loop Trail:

- Javelinas

- Lizards

- Blue Palo Verde

- Saguaro Cactus

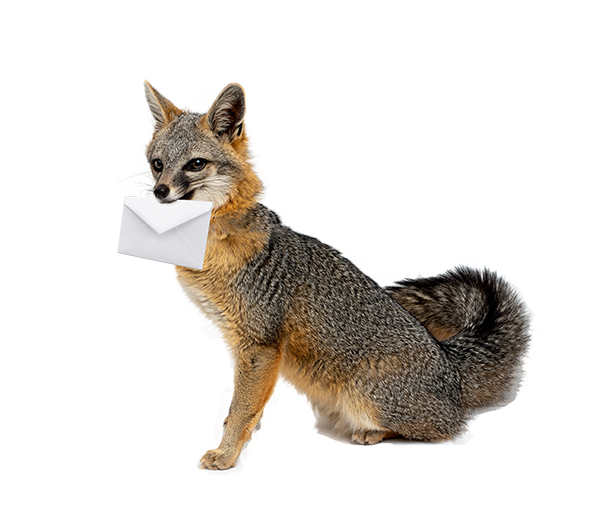

Coyote

The coyote is without a doubt the most famous desert animal, the very symbol of the west. He is prominently figured as the Trickster as well as the Wise One in Native American myths and legends. The coyote fascinates us with its intelligence and adapability. It can survive eating anything from saguaro fruit to roadkills, and is able to live in any habitat from cactus forest to the city. The coyote has expanded its range throughout the United States despite human attempts to eradicate it. The coyote is not only intelligent, curious and playful, it has very keen senses that adapt it for survival-acute hearing, excellent vision, and an extremely sensitive sense of smell.

Coyotes are mostly social animals, living in small family groups. Within the larger hunting area of a coyote family is a central core area where the den sites are located. This area is scent-marked and defended, particularly during the spring and summer months. Coyotes urinate on bushes or other plants, then scrape the ground with their paws, which have scent glands. This leaves both olfactory and visual markers for other coyotes. Scats are also used to mark the territory.

Coyotes typically sing a "good morning" wake up song around dusk as they prepare for the night's hunt. They also sing to communicate with neighbors, to keep track of family members, after summer rains, during the full moon, and it seems, just for fun.

Javelina

Javelina meander in loose groups, feeding as they move through an area. They dig up roots and bulbs with their sharp hooves or with their snouts. They eat prickly pear cacti, spines and all, by tearing off bites with their large canines. Because they don't have sharp cutting teeth, much fibrous material is left on the prickly pear. Javelina chew as they walk, so bits and pieces fall from their mouths, sometimes leaving a short trail.

Javelina live in groups of 2 to 20 animals, the average being about 8 to 12. Each group defends a territory of about 700 to 800 acres, the size and boundaries varying in different seasons and different years; the territories include bed grounds and feeding areas, but they may overlap at critical resources, especially watering holes. An older, experienced sow leads the herd, determining when to bed down, feed, or go to water. Javelina have no defined breeding season; the babies, usually twins, can be born in any month. Not many predators other than a mountain lion will attack an adult javelina, but the babies are also prey for coyotes, bobcats, and other animals.

Javelina have poor vision, relying instead on their sense of smell.

Blue Palo Verde

The green bark color of palo verdes is due to chlorophyll-bearing tissue. As do many other species, these trees conserve water by dropping their leaves during dry seasons, but palo verdes can still carry on some photosynthesis. Blue palo verde also drops its leaves in response to cool autumn temperatures.

The flowers are pollinated by numerous species of solitary bees that gather pollen and cache it in burrows for their grubs to feed on. The main palo verde bee is Centris pallida, but there are 6 other species of Centris that visit palo verdes, in addition to sweat bees, several leaf-cutter bees, bumblebees, and carpenter bees. Bee specialist Bob Schmalzel casually identified about 20 different species of bees foraging in a single palo verde tree at the same time.

Saguaro

The huge green columns of saguaros have captivated the attention of nearly every tourist who has set eyes on one, let alone a whole "forest" of them. The United States has even devoted a national park to this plant. Saguaros are even more important to the O'odham peoples who have lived in their habitat for centuries. The high esteem O'odham have for saguaros is reflected in their many creation stories for this plant, which tend to share the common theme of people being turned into saguaros. These giant cacti are not plants to the Tohono O'odham; they're another form of humanity.

The saguaro is the largest cactus in the United States, commonly reaching 40 feet (12 m) tall; a few have attained 60 feet (18 m) and one was measured at 78 feet (23.8 m). The cylindrical stems are accordion-pleated; the ridges (outer "ribs") are lined with clusters of hard spines along the lower 8 feet (2.4 m) and flexible bristles above this height. White flowers are about 3 inches (8 cm) in diameter; they bloom mainly in May and June and are followed a month later by juicy red fruit.

The saguaro's range is almost completely restricted to southern Arizona and western Sonora. A few plants grow just across the political borders in California and Sinaloa. Saguaros reach their greatest abundance in Arizona Upland. Plants grow from sea level to about 4000 feet (1200 m). In the northern part of their range they are most numerous on warmer south-facing slopes.

Water comprises most of the weight of the saguaro. A fully hydrated large stem is more than 90 percent water and weighs 80 pounds per foot (120 kg per meter).

The great, mostly aqueous bulk of larger plants protects them from temperature extremes. Heat absorbed through the surface during the day is stored in the mass of interior tissue, resulting in a fairly small temperature rise that doesn't reach a lethal level. The heat is slowly radiated and conducted back into the air during the cooler night. The same thermal inertia usually keeps the tissues above freezing on cold winter nights.

Saguaros flower mostly near the stem tips during the dry foresummer; peak production is from mid-May to mid-June. The sturdy white flowers open late at night and remain open until midafternoon of the next day. They are about 3 inches (8 cm) in diameter and emit an aroma like that of overripe melon. The flowers are self-sterile; cross-pollination is necessary for fruit set.

The fruit ripens in tremendous abundance during the peak of the foresummer drought, and is nearly the only moist food available during this hottest, driest time of the year. It becomes a staple for many birds, mammals, and insects during late June and early July. The primary effective seed dispersers are several species of fruit-eating birds, such as White-winged Doves, Gila Woodpeckers, and House finches. The birds digest the pulp, and the seeds pass through their guts intact. Birds also tend to defecate while perched in trees, thus depositing the seeds in favorable environments for establishment.

Seedlings grow very slowly during their first few years and are extremely vulnerable. They are tiny, heat- and frost- tender, soft-spined canteens. Rodents, rabbits, and birds eat the seedlings they can find, and many others succumb to desiccation or winter freezes. Nearly all survivors are located beneath the canopies of nurse plants, where they are sheltered from weather extremes and concealed from herbivores. Most desert plant species-not only saguaros-must begin life under nurse plants. Creosote bush, bursage, and desert zinnia are among the few perennials that can successfully establish in fully exposed sites.

In the Tucson Mountains, which averages 14 inches (355 mm) annual rainfall, a saguaro takes about 10 years to attain 1¼ inches (3.8 cm) in height and 30 years to reach 2 feet (61 cm). Saguaros begin to flower at about 8 feet tall (2.4 m), which takes an average of 55 years. Compare this with 40 years to first flowering in the wetter eastern unit of Saguaro National Park (16 inches, 406 mm, average annual rainfall) and 75 years in the drier Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (9 inches, 230 mm). No one has studied the populations near Yuma, which receive about 3¼ inches (90 mm) average annual rainfall.

Saguaros may begin to grow arms when the plant is between 50 and 100 years of age (in the Tucson Mountains), usually just above the stem's maximum girth at about 7 to 9 feet (2.1 to 2.7 m) above-ground. The number of arms and overall size of a plant seem to be correlated with soil and rainfall. Saguaros on bajadas with finer, more water-retentive soils tend to grow larger and produce more arms than do those on steep, rocky slopes. A few saguaros have been observed with as many as 50 arms; many never grow arms. Saguaro arms always grow upwards. The drooping arms seen on many old saguaros is a result of wilting after frost damage. The growing tips will turn upwards in time. There is a myth that arms are produced so as to balance the plants, but research shows arm-sprouting to be random. Many saguaros can be found with several arms all on the same side of the main stem.

Saguaros make excellent nesting places for many birds. The primary nesting associates are Gila woodpeckers and gilded flickers, both of which excavate nest holes in the fleshy stems. The plant seals the wound with scar tissue called callus, which quickly becomes very hard and impervious to microbial infection.

Woodpeckers usually excavate new nesting holes each year. Several other hole-nesting but non-excavating birds occupy abandoned woodpecker nests, including elf owls, house finches, ash-throated flycatchers, and purple martins. Invertebrates also inhabit them.

Larger birds such as red-tailed hawks build nests in the angles between the main stems and the arms. Tall saguaros also make good hunting and resting perches for many birds. Cactus wrens sometimes nest among the arms or, less often, in a woodpecker cavity.

Fallen saguaros become homes for many small animals. Snakes, rodents, lizards, and invertebrates find shelter beneath and within them, until the community of reducers and decomposers completely recycle the remains.